DataLog: Art Encoded is curated by Jane Edmundson, and generously funded through the Alberta Foundation for the Arts Emerging Curator Fellowship. Click through the images in the exhibition above, then scroll down to learn more about the pieces.

Explore this exhibition on Google Arts & Culture.

“The medium is the message.”

-Marshall McLuhan, Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, 1964

Our online experiences are mediated by streams of code that most of us never see. This invisible data facilitates all of our technological interactions and enables work, entertainment, education, and creation. The off/on, negative/positive Boolean patterning of binary computing code is a contemporary cousin to the printing press, Pierre Jaquet-Droz’s 18th century automatons, and the Jacquard Loom. The relationship between technology and creative production is visible today in Photoshop hobbyists,Maker Faires, and the coded meanings of conceptual art.

The ability to instantly access a wide variety of information and platforms for an enriched, interactive experience is one not easily achieved by an exhibition in a conventional, physical art gallery space. DataLog : Art Encoded fully embraces and uses the resources of the digital realm to exhibit selected artworks from the AFA Collection while discussing the existence of art inside the technological landscape. The selected artworks employ patterning, code, negative/positive space, layering and pixelation to deliver messages to the viewer that are further influenced by the online platform that gives us access to them. The interdependent relationship between information and the technologies that facilitate its spread was predicted by Marshall McLuhan in pre-internet 1964, when he argued that the structure of a medium influences the way the messages it delivers are perceived. McLuhan believed that the information we receive is altered by the type of platform that delivers it to us; that knowledge consumed via book, radio, television, or computer, will be remembered and used differently.

DataLog : Art Encoded is organized into three thematic sections – ‘01100001 01110010 01110100’, ‘[re]generation of the image’, and ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction’ – that explore concepts applicable to the worlds of both art and technology, including coded meaning, absence/presence, Pointillism, obsolescence and the evolution of visual media. Walter Benjamin’s influential 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” is re-examined within the context of digital creative methods and held up as a mirror to current discussions around artistic authenticity in a technologically-mediated age. Hyperlinks to related articles, YouTube videos, artist websites, interactive portals and streaming apps situate the selected artworks within the diversified multimedia of contemporary life, where our browsers (and brains) regularly have countless tabs open simultaneously.

Artwork Descriptions

01100001 01110010 01110100

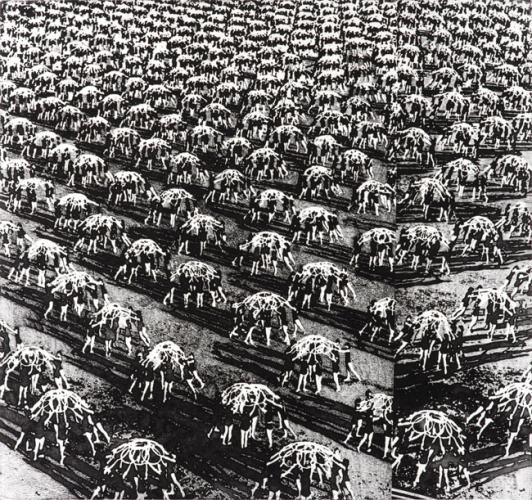

Jane Molnar, Hoola Hoopers, 1979, photo-engraving on paper, 1981.068.001

Molnar’s repeating clusters of figures holding hula hoops are reduced to the bare contrasts of greyscale in this optical-illusory print. The white spaces of arms, legs, and hoops blend together against the black and grey shadows as the figures become exponentially tinier, disappearing into the perspectival plane of the image. As the viewer’s eye travels into the image’s depth, the figures give way to abstraction, creating a pattern of positive and negative space.

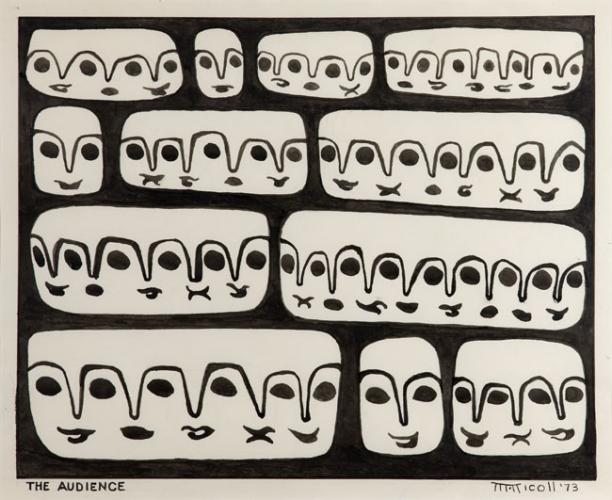

Marion Nicoll, The Audience, 1973, ink on paper, 1981.155.218

Nicoll is most known for her hard-edge abstractions, but the repetition of curving lines and circles in The Audience communicate the essential, stylized features of faces. The shapes are further anthropomorphized by gestural strokes added beneath the “noses,” breathing personality into a highly simplified and stripped-down composition that ties this drawing back to Nicoll’s large-scale abstract paintings.

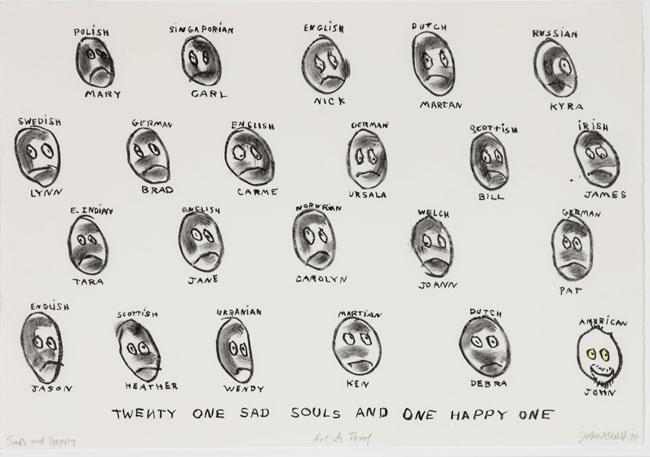

John Will, Sads and Happy,1994, lithograph on paper, 1999.118.016

The binary opposition created by Will in this lithograph stacks his American-bred happiness against the frowns of 21 international faces. Will’s art practice is tongue-in-cheek and often uses autobiography as source material. Despite his statement that much of his work is “about nothing”, Will frequently draws on philosophical thought, art history, and politics, punctuating headier concepts with absurd excerpts from daily conversation. As a sort of self-portrait, Sads and Happy positions the artist as the literal “one” amongst emotional zeroes.

Mary Kavanagh, Tarnish: Silver Drawings, 2005, linen napkins, silver polish residue, tags, 2009.056.001

Tarnish is the conceptual twin to Kavanagh’s polish, where a long table of 1000 silver-plated household objects were displayed in the gallery space. The items were collected by the artist over a three-year period from prairie flea markets and antique shops, and painstakingly classified and labeled with identification tags. A linen napkin was assigned to each object and over the course of exhibition in four venues, the silverware was polished clean. The traces of the performances are made visible in tarnish, where the dark remnants of domestic, repetitive action stand out against the stark white napkins. Kavanagh sewed the cloths together to form a tapestry that brings to mind a quilt, or the clean tablecloth that the objects were initially displayed on.

Eric Cameron, Thin Painting: Chris’s Thread and Needle, 2007, acrylic gesso, spool of thread, needle, 2009.041.001

Cameron has been creating a body of work he calls “thick paintings” since 1979. Everyday objects are covered in hundreds of layers of gesso that he applies on a daily basis, brushstroke by brushstroke. Each coat of acrylic marks the passage of time, and contributes to the evolution of a pair of shoes, a rose, a head of lettuce (or in this case, a needle and spool of thread) into mysterious and amorphous sculptures. The object at the core of the sculpture ceases to exist in its original form, translated by its shroud of paint and requiring a new language to be read.

[re]generation of the image

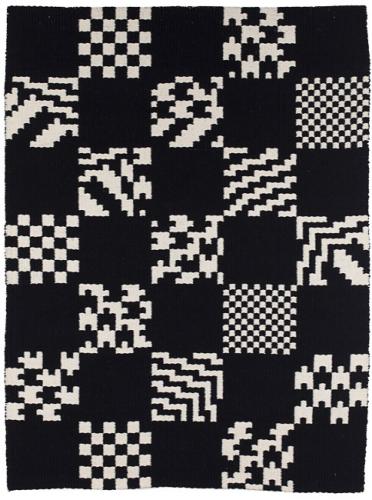

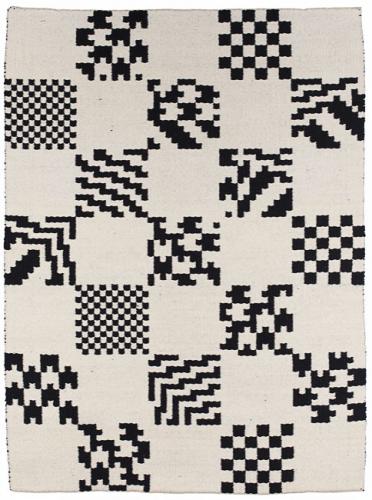

C. Bryn Pinchin, Pieced of an Image, 1988, woven wool, linen, 1989.106.001.V&R

Pinchin’s weaving predates the computerized manipulation of images that we have grown accustomed to in media, advertising, art, and our personal snapshots, but still captures the hard-edged patterning of pixelation associated with digital files. The textile is designed to be viewed from both sides, creating a positive/negative, inverted spectrum mirror. The interlocking threads of black and white wool make a gridded image that brings to mind both analog newspaper printing techniques and our contemporary computer screens and smartphones.

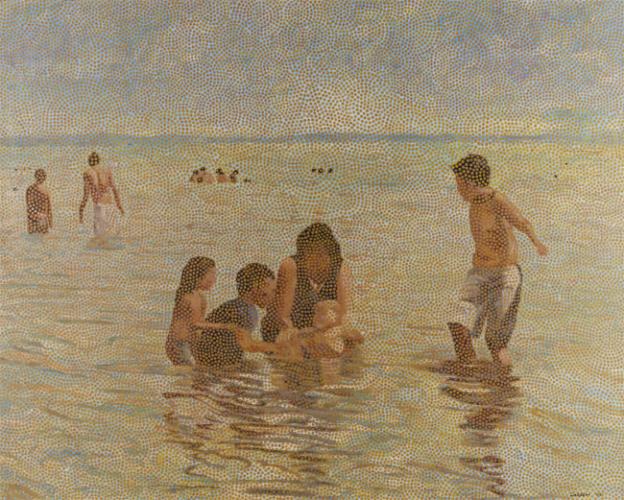

David Garneau, Lac Ste Anne, 2008, acrylic on canvas, 2009.021.001

Garneau draws on a 19th century optical painting technique to capture a dreamlike atmosphere in Lac Ste Anne, named after the pilgrimage of great spiritual significance to the Cree and Métis peoples of Central Alberta. Pointillism harnesses the human eye’s ability to blend distinct dots of contrasting colours into tonal planes, creating gradients of light and shadow that can be perceived as depth. The same principles are used in CMYK printing and RGB television and computer monitors. Garneau builds this image by overlaying a swirling pattern of dots in neutral tones over simplified shapes painted in a warm palette, communicating the memory of a fleeting moment of family bonding and sacred healing.

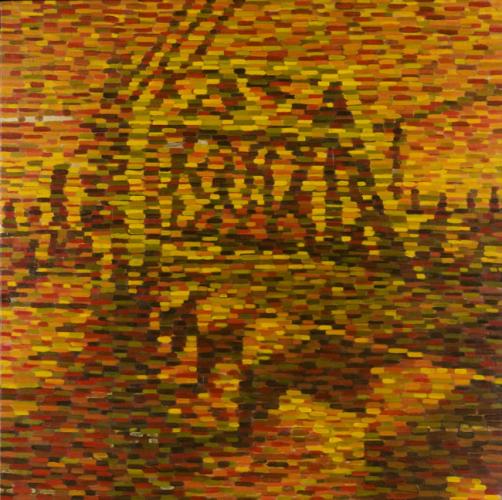

Elliot Engley, Walterdale Bridge, 2008, acrylic on canvas, 2010.011.001

Rendered in an autumnal palette and thick, horizontal brushstrokes, Engley’s Waterdale Bridge brings to mind a TV channel half-lost to static, or a MagicEye autostereogram where the two-dimensional plane obscures a secret image of depth. When viewed up close, the architectural elements dissolve into an Impressionistic patchwork; at a distance, the image falls into focus, allowing the painting to serve as a record of the century-old thoroughfare that spans the North Saskatchewan River in Edmonton. The Impressionists aimed to capture temporary moments in time and space; similarly in Waterdale Bridge, Engley chooses to visually preserve an urban landmark that is scheduled for demolition in 2015/2016.

Chris Cran, Gold Woman 2, 2012, enamel, acrylic gel on board, 2013.004.001

Created as part of his recent Chorus series, Cran’s Gold Woman 2 is a hybrid of techniques and concepts the artist has been working with throughout his career. Cran has moved between photorealism, formalism, Op and Pop Art for over 30 years; his canvasses hover between representation and abstraction. Cran often uses blown-up imagery from the cartoons and advertising of the 1950s and 60s that were originally made with the Ben-Day dot analog printing process, regenerating these images to simultaneously form and dissolve in the eye of the viewer.

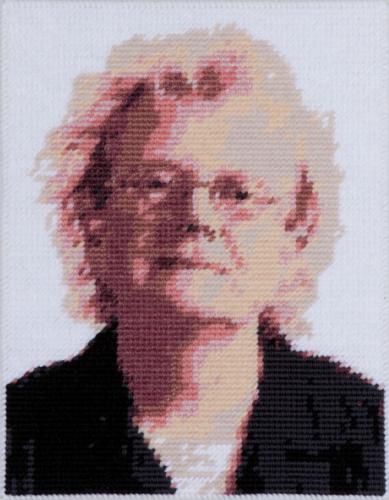

Megan Morman, Rita McKeough (Calgary), 2010, mixed-fibre yarn on plastic canvas, 2013.021.001

In her portraits of queer contemporary Canadian artists, Morman translates the pixelation of digital photographs into stitches of brightly-coloured yarn and fusible plastic beads. To immortalize Calgary-based art star and musician Rita McKeough, Morman used the gridded framework of “plastic canvas” needlepoint crafts (a common craft material for children of the 1980s). The resulting fuzzy edges and terraced gradients recall the graphics and animations of the early Internet, the work’s kitschy combination of craft and outdated tech triggering warm feelings of nostalgia.

The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction

“... for contemporary man the representation of reality by the film is incomparably more significant than that of the painter, since it offers, precisely because of the thoroughgoing permeation of reality with mechanical equipment, an aspect of reality which is free of all equipment. And that is what one is entitled to ask from a work of art.” – Walter Benjamin

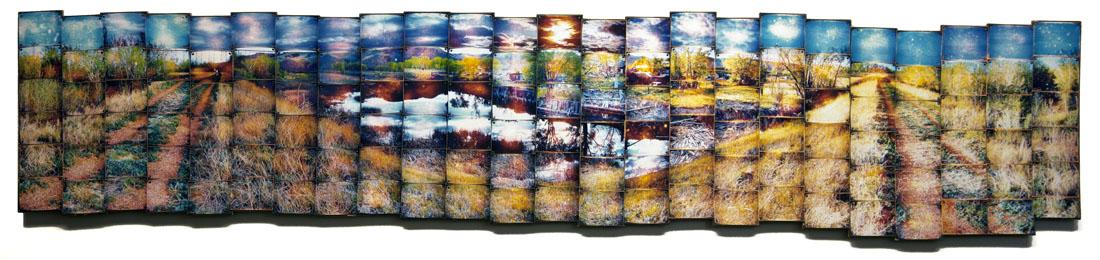

David Hoffos, Nature Walk, 1995, colour photographs, nail on plywood, 1999.001.002

The collaged photographs that make up Nature Walk both capture a sense of place and document fleeting moments in time. The highly saturated colours transport the viewer back to a sunny day, but as the grid becomes imperfect across the rolling hills, the memory is fragmented. Hoffos’ combining of photographs shot in sequence predates current digital panoramic stitching software, while following the tradition of the painted panoramas and cycloramas of the 18th and 19th centuries. The “mechanical equipment” used by Hoffos is made plain by the individual snapshot size of the photographs, fabricating a hyperreality that, instead of being “free” of mechanism as Benjamin describes, makes the process of its creation clear.

“Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be. This unique existence of the work of art determined the history to which it was subject throughout the time of its existence...The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity.” – Walter Benjamin

Faye HeavyShield, rock paper river, 2005, paper, digital photography, wax, 2009.141.002

rock paper river challenges Benjamin’s statement that reproduced images lack the capacity to embody authenticity and presence, as in this case (and in much of HeavyShield’s artistic practice) the “original” is made of many reproductions of digital photographs. HeavyShield often incorporates geographical elements into her work to reflect on her personal history and the cultural lineage of the Kainai Nation. References to the connection between land and body are visible in her most recent installations, where monochromatic photographs of skin, earth, and water are printed onto paper that is then folded or cut into multiplying, minimalist forms. The spatial relationships she creates between the viewer and the objects in these environments foster the “unique existence” Benjamin advocates; an authentic presence enabled, rather than prevented, by the reproduction and multiplication of the “original” image.

“Distance is the opposite of closeness. The essentially distant object is the unapproachable one. Unapproachability is indeed a major quality of the cult image. True to its nature, it remains "distant, however close it may be." The closeness which one may gain from its subject matter does not impair the distance which it retains in its appearance.” – Walter Benjamin

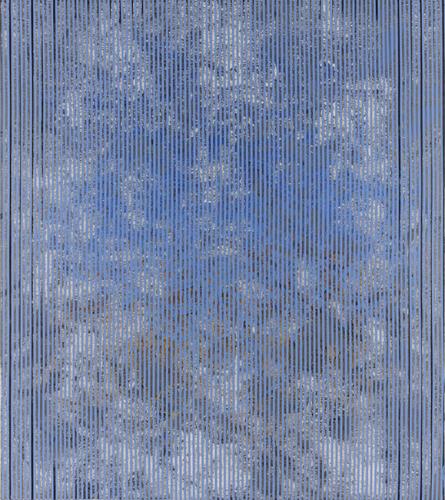

Geoffrey Hunter, Cloud Nine, 2014, acrylic on canvas, 2014.017.001

Benjamin refers to a philosophical distance between the viewer and the elevated, authentic work of art. Hunter’s Cloud Nine creates an optical distance with a layered screen of lines that partially covers the familiar image of a realistic cloudscape. Hunter achieves the illusion of depth in his paintings by applying and scraping away layers of paint in geometric patterns laid over top a source image, referencing both the history of Neoclassical art and contemporary digital image manipulation. The space between the viewer’s eye and the artwork compresses with the struggle between the representation of the sky in and among the abstraction of repeating vertical bars.

“A painting has always had an excellent chance to be viewed by one person or by a few. The simultaneous contemplation of paintings by a large public, such as developed in the nineteenth century, is an early symptom of the crisis of painting, a crisis which was by no means occasioned exclusively by photography but rather in a relatively independent manner by the appeal of art works to the masses.” – Walter Benjamin

Shelley Ouellet, Johnston Falls, 2012, plastic beads, plastic wrapped steel wire, 2014.030.001

Benjamin’s argument that the aura of painting was depleted once artworks began to be contemplated by a large public has interesting implications when applied to 19th century campaigns that used landscape paintings to promote Canada to a wide, international market. Picturesque nature scenes of unpeopled lands were made to sell the concept of a Canada ready for European consumption (despite the reality that many of the “empty” landscapes were already occupied by First Nations peoples). Johnston Falls is the follow-up to Ouellet’s Wish You Were Here… beaded curtain series that draws on historical paintings by artists Lucius O’Brien, Fredrick Edwin Church, and Frederic Marlett Bell-Smith. Ouellet replicates these icons of Canadiana on a grand, glittering scale to examine our relationships with constructed national identity, tourism, and an idealized natural world. She has employed computer mapping in the planning and assembly stages of her work since the mid-1990s, breaking source images into gridded components based on colour palette and then constructing the reproduction out of diverse, mass-produced materials including activist ribbons, plastic bugs, sequins, and Lite-Brite pegs.

“Mass reproduction is aided especially by the reproduction of masses. In big parades and monster rallies, in sports events, and in war, all of which nowadays are captured by camera and sound recording, the masses are brought face to face with themselves. Thls process, whose significance need not be stressed, is intimately connected with the development of the techniques of reproduction and photography. Mass movements are usually discerned more clearly by a camera than by the naked eye....This means that mass movements, including war, constitute a form of human behavior which particularly favors mechanical equipment.” – Walter Benjamin

Jonathon Luckhurst, Mudbank V, 2010, silver gelatin fibre print, 2010.055.001

Luckhurst uses the mechanical equipment of film-based photography to communicate subtleties in human interaction and the divide between built and natural environments. His commitment to traditional photographic methods in the midst of the popularity of digital cameras and software has commonalties with Benjamin’s belief in the authenticity of classical artistic methods over technological reproductions. Ironically, Luckhurst remains faithful to film-based techniques that, in Benjamin’s time, were viewed as a threat to artistic authenticity – what was once new and considered dangerous to the lineage of fine art is now, in some circles, seen as protecting it from the invasion of Photoshop hobbyists. In Mudbank V, however, Luckhurst does depict the subject Benjamin argues is most suited to photography – the mass movement of human bodies. But unlike literal reproduction or stark documentation, Luckhurst aims to inspire an emotional response in the viewer by prompting the degradation of the image, where people in the crowd are rendered anonymous by blurring, grain, and interventions in the printing process.